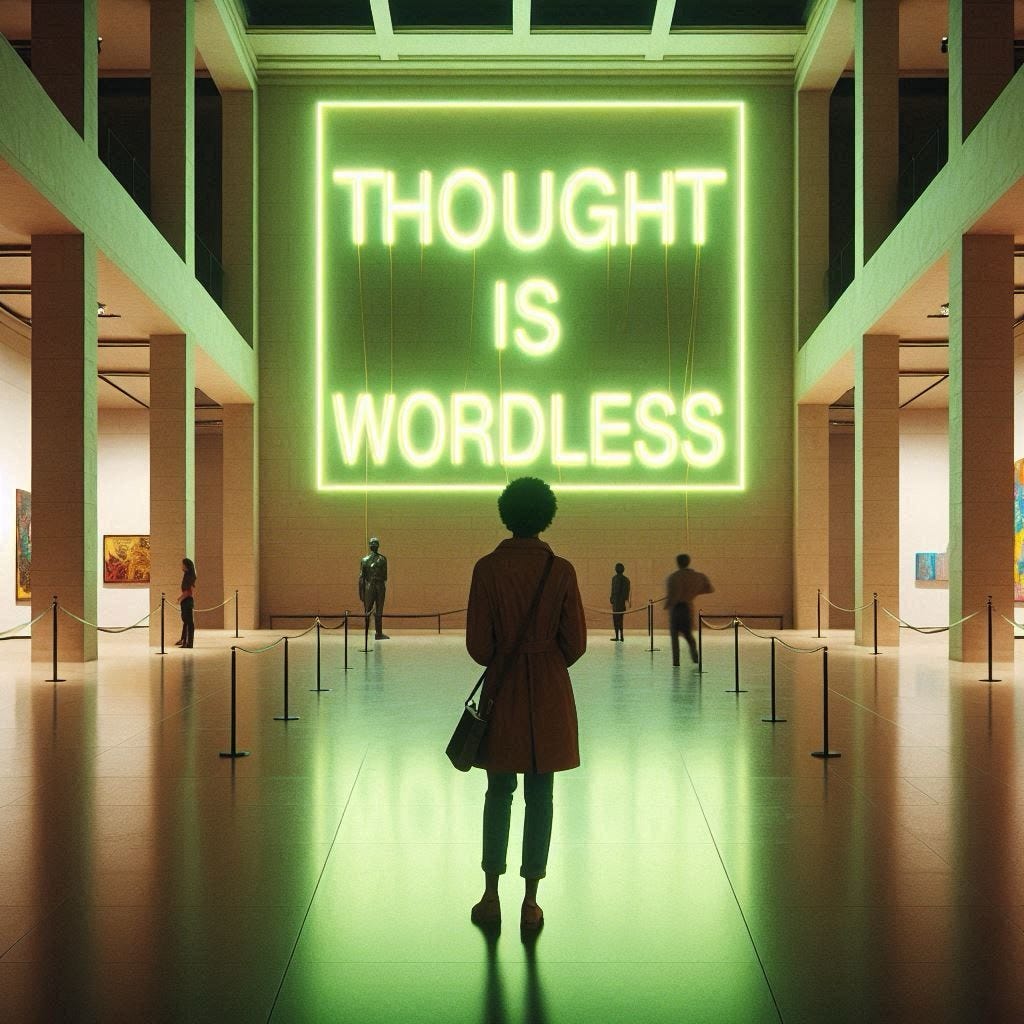

An Astounding Idea

Correcting a fundamental misunderstanding about writing

Barbara: Here’s a question for you. Do you think that you think in words?

Elizabeth: I’ve always assumed that I do. That’s certainly how it seems.

Barbara: Well then, you’ll be surprised to hear about some new research on this topic, demonstrating that people do not think in words. The paper, in the journal Nature, reported on findings showing that, when people are simply thinking, the language parts of their brain are not active. In other words, neurologically, thinking and language are distinct. Language is optimized for communication. We think that we think in words … but we don’t!

And this new insight has implications for writers, for all of us who use language to express ourselves. The ideas in this paper add to our understanding of how the brain writes — a glimpse at what might be going on neurologically in the background as we write.

Elizabeth: This is hard to get my head around. Let’s take a giant step back. What exactly do you mean by “think” or “thought”?

Barbara: A succinct definition might be something like…thought includes all of one’s knowledge of the world, based on experience and learning, and then reasoning and predicting based on this knowledge. And all of it is non-verbal.

Elizabeth: How about a less “succinct” definition?

Barbara: Well, you know what it was like to grow up in your family or that the tree branch is moving because of wind. But, less obviously, you also know how heavy your cup of coffee is, so that you pick it up with the precise amount of upward pressure required. And that kind of predicting, based on past experience, is going on continuously, automatically. Most of what you see, for instance, is what you expect to see, and when it isn’t, you notice. Even infants notice when a ball rolls uphill! This is a much more efficient way of going through the world than having to analyse every single scene you encounter.

Elizabeth: It’s logical that that kind of knowledge is non-verbal, but what about all the facts you have accumulated and all the words you have learned to name things and to express emotion and abstract ideas? Surely these thoughts are in words.

Barbara: Well, certainly you have “linguistic” knowledge. But the processes of knowing what something is (something you sleep on) and of being able to name it (bed), while working together in a healthy brain, are separate functions. We know this from studying patients who have lost one or the other ability.

And there is internal speech. Sometimes we talk to ourselves in our minds; we recite poems, rehearse a speech… And some people “hear voices.”

The rest of inner thought, though, be it reasoning, inference, fundamental social knowledge, expectations, hopes, dreams, images, calculations, images…is all non-linguistic. And by that I mean, it is not only wordless, but it also lacks the kind of inherent structure that language has.

Elizabeth: So, you are saying that in order to work with and communicate inner thoughts writers have to transform them into words.

How hard is this? Isn’t the thought-to-word process itself essentially automatic? You’ve pointed out that for the most part we don’t know what we’re going to say until we say it, and that process feels instantaneous. Isn’t this transformation of thought-to-word when we’re writing the same thing?

Barbara: Yes it is. But much of the time, especially when speaking, what we want to communicate is pretty simple, and putting thoughts into words then feels effortless. But, when the thoughts are complicated, then words don’t come so readily. And when the ideas we have are not only complicated but also foggy and unformed, writing becomes the vehicle by which we figure out what we wanted to say all along.

Consider how other creative individuals who express inner thoughts non-verbally work out their ideas. A painter uses paint; a musician, sound; a dancer, the body. We each use the medium of our work to help us think. And for a writer, the medium is language (to quote a friend of mine, Meg Cambell!). When we want to say something that is complicated or that we only have an inkling of, initially we literally do not have the words to communicate what we’d like to express.

Elizabeth: So you’re saying that we have to find the words. This sheds a lot of light on why first drafts are usually so bad… and why editing and more editing are so essential for most of us.

Joan Didion famously said, “I write in order to know what I think.” That may not be every writer’s explanation for why they write. But apparently it is the process writers use who are not simply reporting: we learn what we think by writing or verbalizing our thoughts.

Barbara: Larry McEnerney, when he was Director of the University of Chicago’s Writing Program, addressed this issue directly in a lecture to help graduate students write papers more likely to be accepted for publication:

“You are operating at the most sophisticated level…. thinking stuff no one has ever thought before. The thinking that you’re doing is at such a level of complexity that you have to use your writing to help yourself think.”

McEnerney was flattering his audience, but his message is true for anyone doing original writing — fiction, non-fiction, anything. In fact, he went on to explain how his own high school teachers had not understood the concept. They’d instructed him to first figure out what he was going to say, then produce an outline, and only then write the paper — to first think and then write. They’d had it backward. He wondered if he was the only student who secretly wrote the paper before the outline.

Elizabeth: This fits my experience. I usually start to write with only a vague sense of an idea worth thinking through, a dim light in the fog. First, I make a stab at getting the notion into words, after which I can see a path forward. Then, I work out the idea for myself by editing.

Barbara: This totally corresponds to what the paper says, that there are wordless mental processes (thoughts) going on that don’t use the language networks of the brain. So, writing is giving birth to what stirs inside you, what bubbles up, so to speak.

But, much of the time, especially when speaking, we go very quickly from thought to words. That’s one reason for the longstanding debate about whether thought is separate from language.

Elizabeth: Now research seems to have settled the debate. I just have to say, the whole process of going from a miasma of vague notions to, say, a clearly articulated essay seems almost magical.

This makes me think of Helen Keller. She lost both sight and hearing at 19 months and had no language until she was seven, when she met her teacher, Anne Sullivan. In Keller’s autobiography, she describes herself as having been “at sea in a dense fog.” Before Sullivan, she could only communicate with her family by using hand movements.

Barbara: But, that wasn’t language! She hadn’t yet learned the fundamental notion that things (objects, actions, feelings, sensations, etc.) have symbolic representations attached to them — namely words! — whether those words are sounds or gestures, as in sign language.

Elizabeth: Here is her description of the moment she grasped the concept of language, something she’d struggled with for several weeks, while Sullivan wrote words into her palm:

I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten—a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that w-a-t-e-r meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. The living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, set it free!

Before that, Keller’s knowledge of the world came through senses other than hearing and sight. She knew her family members by touch and could distinguish the vibrations of their footsteps. She could smell flowers and baking bread. Her mind was full of thoughts — before she had a single word for anything at all.

—-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you enjoyed this essay, please let us know by using one of the three options below: like, comment, share. Reader activity is key to getting Substack to promote our newsletter. Even a click on “like” counts as activity!

Very, very cool. And, when you think about it, it makes sense, because babies must think long before they start talking.

Astounding! Thank you. Is all of the brain used to think? If the language area doesn’t light up, what does? Is this in the Nature paper?