Elizabeth's Story Explained — Part 1

Powerful memories can include emotions and one’s earlier state of mind.

Elizabeth: In our last post, I related the very strange story of how my writer’s block dissolved in an instant when I inserted, into the opening scene of my manuscript, a parenthetical phrase that declared my need to speak. And I asked you how merely adding those few words to a scene in which I was stifled could have had such a dramatic effect.

Barbara: We could discuss many different aspects of your experience. But the first thing to explore is the “mental place” you were in when you experienced this resolution of your writer’s block. I realize that you were sitting at your computer in Boston, but mentally you had gone back to your parents’ dinner table and to a particular moment in time. The phrase you inserted had the effect it did, first of all, because of the state of mind in which you felt trapped.

Elizabeth: I had certainly returned mentally, emotionally, to the scene I’d recreated in words. I was there, in my place at the table, just as I had been all those years earlier. My parents were alive again, and I was once again “shut down” in their presence.

Barbara: And all of that tension and drama was occurring in your mind. You do have a remarkable ability to vividly call up memories — which not everyone has to the same degree. You described yourself as reliving that Thanksgiving scene, not simply remembering it, which is how people describe their traumatic memories.

In fact, some studies that look at brain activity have shown that traumatic memories are not simply more emotional or more fear-filled than other types of memories. Traumatic memories seem to be processed in a fundamentally different way. They are not mapped or linked to other events within an associated time and space framework as non-traumatic, episodic memories are. In other words, traumatic events are not linked to one’s past timeline of experiences, and, when they intrude into mental life, it is as though they are being experienced in the present.

Elizabeth: I’ve never thought of myself as someone who’d been traumatized, given the horrific traumas people endure. But I certainly was terrified of my mother and watched her humiliate others.

Barbara: So when you actively and purposely conjured up your family gathered around the Thanksgiving table, you relived it. You not only “remembered” it in a purely cognitive sense but also you went back to some extent to how you once experienced it, with many of the associated physical sensations and emotions. For you, that meant again becoming unable to speak up.

In therapy, it can be overwhelming for people to talk about their past traumas. Traumatic memories have other notable characteristics. They may be fragmented, with only parts of what happened accessible to memory. They also can intrude, unbidden. And they tend to be walled off, embalmed, and don’t necessarily get amended naturally as you mature and gain new knowledge, new perspectives.

Elizabeth: It makes sense to me that early, painful memories live on as you first experience them and that these memories have a grip on you and continue to influence your behavior in ways that you might not realize. That is certainly my experience. The memory of being shut-down arose from peering for a very long time into that Thanksgiving scene in my mind’s eyes. But I’ve also used another technique to dig under the surface when trying to bring a scene to life on the page.

Many years ago, I saw a psychiatrist who suggested that his patients stare at a childhood photo, as a way of connecting with their younger selves. I did the exercise, and after a while I began to sense confusion and fear in the little girl in my photo. I remembered/imagined how it felt to be that little girl. The following question came to mind: “What do they want from me?”, which I recognized as my childhood response to my parents’ chronic dissatisfaction with me. Meditating on the photo allowed me to put words to the complex feelings behind the cloud of confusion that had always been there.

Barbara: You found a way to connect with what you always knew you had felt but had never put into words. You essentially tapped into a complex feeling state and translated it into words.

I do want to add a very large dose of caution here. Memories are not snapshots of the past; they are not entirely veridical. Perhaps we ought to do a post on memories! Each time one calls up a memory, that memory is recreated, though, of course that’s not how it feels. But, for writers, it is useful to find ways to access the complexity of past experiences in order to bring their writing alive, whether in memoir or fiction.

Perhaps it would be useful to point out here that psychologists have known for a long time that memories are more apt to be recalled when you are in the same mental state or physical context as when the encoding of the memory occurred. This is called “state-dependent” or “context-dependent” recall.

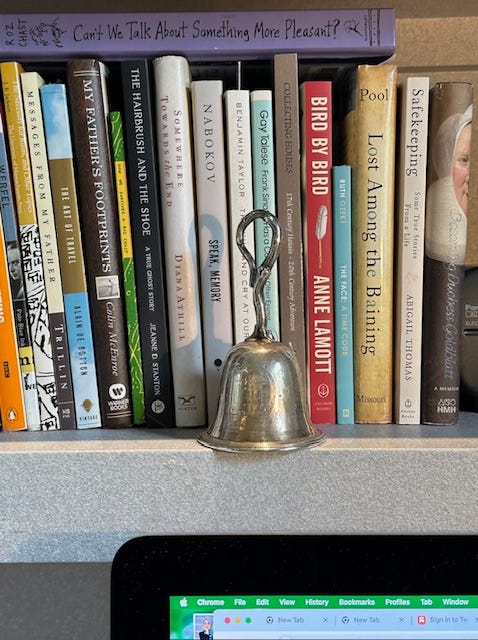

Elizabeth: Objects can do this, as well. One of the things I took from my parents’ home, after they’d died, was my mother’s silver dinner bell. Hard as it may be to believe today, in the 1950s many families with an extra bedroom could afford live-in help and needed it if the mother worked full time, as mine did. Eventually, when I outgrew requiring childcare, Amy, my beloved nanny, daughter of Nova Scotian lobstermen, became the cook. This did not go smoothly, as she’d had no previous cooking experience whatsoever!

The bell was how my mother summoned her to the table, to remove or to bring a dish — or to receive her relentless criticisms. I never spoke up during these nightly scenes. Defending Amy was not an option; my mother would have gone ballistic. She might even have fired Amy(!), or so I feared.

So, the bell has tremendous evocative power for me. Later, when I was working on my memoir, I put it on a shelf over my desk for inspiration. Occasionally I held it. But I could never bring myself to ring it.

Barbara: Places can have this power, too. There’s a wonderful example of this in Turn Every Page, a film about the relationship between the history writer, Robert Caro, and his editor, Robert Gottlieb, made by Gottlieb’s daughter. Caro was writing a book about Lyndon Baynes Johnson and had interviewed his brother, Sam Houston Johnson. But Caro had been unable to get him to share more than the same empty, superficial stories he always told about their childhood.

In the film and in an interview with Kurt Vonnegut, Caro recounts how he took Houston to the Johnson family home and had him sit in his old spot at the dining table, in the early evening. Caro sat behind him and quietly asked questions, unseen. In time, Houston began to talk, and the truth poured out. Houston’s sitting in that chair and recalling his brother and father in theirs, seeing the shadows fall across the table, brought back all the memories of the rage and animosity between those two. It was so alive for him in memory that, as Caro tells it in the interview,

“He started talking faster and faster. And finally he was shouting back and forth—the father, for example, shouting, ‘Lyndon, God damn it, you’re a failure, you’ll be a failure all your life.’”

Elizabeth: It’s easy to see being flooded with memories in such a situation. Just thinking about my place at the table in the apartment where I grew up makes me queasy: Amy, anxious and teary, the bell, my mother’s mercilessness, my helpless silence and guilt ...

Barbara: Silence. So that’s the context for the parenthetical phrase that freed you from your writer’s block. And that’s why you need to get in your two cents!

The scene at the Thanksgiving table with your preteen children must have been infused with all the dinners when you were their age and Amy had become the cook. Metaphorically, it’s like a Russian doll, with one memory holding an even earlier memory.

Elizabeth: OK, I understand how just reimagining a scene from the past can carry such a wealth of emotion and return you to that previous state of mind. And I understand that the “spell” in which I was caught in the past was dispelled when I showed up as my present self, in the form of the parenthetical remark. But what was the psychological dynamic that made my “showing up” have that effect?

Barbara: Let’s tackle that next week.